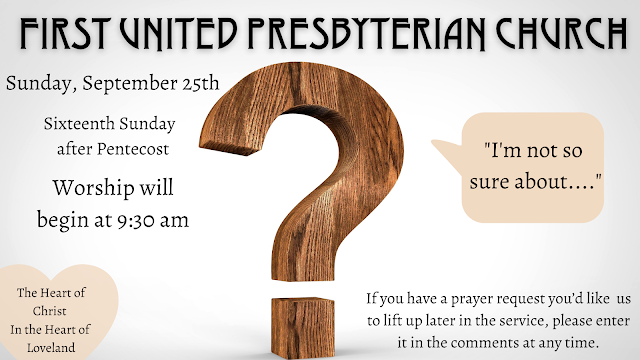

September 25th: “I’m Not So Sure About…God and Government”

First United Presbyterian Church

“I’m Not So Sure About…God and Government”

Rev. Amy Morgan

September 25, 2022

Romans 13:1-7

Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. 2 Therefore whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. 3 For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Do you wish to have no fear of the authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive its approval; 4 for it is God's servant for your good. But if you do what is wrong, you should be afraid, for the authority does not bear the sword in vain! It is the servant of God to execute wrath on the wrongdoer. 5 Therefore one must be subject, not only because of wrath but also because of conscience. 6 For the same reason you also pay taxes, for the authorities are God's servants, busy with this very thing. 7 Pay to all what is due them-- taxes to whom taxes are due, revenue to whom revenue is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due.

Acts 5:27-32

When [the temple police] had brought [the apostles], they had them stand before the council. The high priest questioned them, 28 saying, "We gave you strict orders not to teach in this name, yet here you have filled Jerusalem with your teaching and you are determined to bring this man's blood on us."

29 But Peter and the apostles answered, "We must obey God rather than any human authority. 30 The God of our ancestors raised up Jesus, whom you had killed by hanging him on a tree. 31 God exalted him at his right hand as Leader and Savior that he might give repentance to Israel and forgiveness of sins. 32 And we are witnesses to these things, and so is the Holy Spirit whom God has given to those who obey him."

Here we are again, with seemingly contradictory statements coming from scripture, this time about the appropriate Christian attitude toward authority and government. And we are in dire need of guidance today on the relationship between God and government. Are Christians called to obey all governmental authorities? Or is there no authority but God?

The answer from scripture is yes. There is no authority but God, and all earthly authorities – if they are legitimate, well-ordered, contribute to the common good, and restrict evil in society – derive their authority from God. Those are important “ifs.”

Paul, in his letter to the Romans, is attempting to bring order and harmony to a divided and chaotic church. This small treatise on governmental authority is in response to inclinations toward personal retribution and vengeance. His argument is basically, “it’s more faithful to live in a society governed by the rule of law than by vigilante justice. So pay your taxes and fund the police.” Now, we need to be aware of the fact that Paul has been imprisoned by religious authorities for the proclamation of the Gospel, so perhaps he's hedging his bets with the Roman government at this point. But we also know that Paul’s story ends with house arrest and martyrdom in Rome. And, of course, the Jesus he is preaching about was executed as a political enemy of the Roman Empire. So the authority Paul is encouraging his followers to support is not an authority that is supportive of their faith. But it is an authority that, from Paul’s perspective at this point, is legitimate, well-ordered, contributes to the common good, and restricts evil in society.

Over the centuries, God’s people have existed within a wide variety of political systems. The people of Israel began with a political contract, a covenant. When the Law was given, they operated as a theocracy, more or less. They then transitioned to a monarchy, until they were defeated and taken captive. For generations, Israel lived under the authority of other nations. And they had start figuring out how to operate in that context, how to express their religious convictions without the reinforcement of a political structure. This got worked out in a variety of ways. Sometimes there was a high level of cooperation with governing authorities and even participation in government service. Other times there was open hostility and rebellion. But through all of this, the authority of the religious leadership gets strengthened such that, by the first century, when Jesus arrives on the scene, you have these competing factions of power within the Jewish community with different attitudes toward the Roman government.

We see all of this playing out very prominently in the gospels. Jesus is clearly cast as a political figure. Matthew depicts Jesus as a “New Moses,” raising the expectation of re-instituting theocratic governance, and Mark emphasizes that Jesus teaches “with authority.” Luke endows Jesus with prophetic authority to overturn current power dynamics, and John states that he has God’s authority to execute justice. Jesus is constantly in conflict with the religious authorities, and they frequently confront him with questions about his positions on Roman authority.

The Jews at this point have been relatively quiet about God’s authority on earth. They’ve worked with the Romans, for the most part. But there are some zealots out there causing trouble, wanting to overthrow the Romans and re-establish the kingdom of Israel’s political sovereignty. The Jesus movement in this context takes on a distinctly political nature, and Jesus is very aware of it. He challenges the politics of his own Jewish community and subversively promotes the coming reign of God on earth.

When questioned about paying taxes, Jesus says “give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s.” But then the accusation made against Jesus according to the Gospel of Luke is: "We found this man perverting our nation, forbidding us to pay taxes to the emperor, and saying that he himself is the Messiah, a king."

Even the gospels are unclear about the relationship between God and government.

It’s also important to note that the gospels are all clearly written after the First Jewish Revolt and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. The political tensions of this revolt, which developed out of protest to Roman taxation (if that sounds at all familiar), are all part of the subtext of the political tensions of the Gospels.

In the first few centuries of Christianity, the faith was seen as a resistance movement within the Roman Empire. Christians were often persecuted, and many of them refused to pay homage to the emperor, who was seen as both a political leader and a deity. Devotion to Jesus and citizenship in the Roman Empire were mutually exclusive commitments, and faithfulness to the gospel often came at high personal cost.

But then, in the 4th century, Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and declared Christianity as the state religion of Rome. Suddenly, these mutually exclusive commitments of religion and citizenship became a total merger of church and state. God’s authority and the state’s authority were one and the same. But not in a theocratic sense. Instead of divinely-appointed tribal leaders, legal interpreters, or even kings, the civil authority baptized the Christian religion. The push and pull between ecclesial and political authority is written across the history of Christendom.

So then, when the Reformation comes around, this upsets not just religious apple carts but political ones as well. Political leaders declare allegiance to different religious factions, and brutal and bloody wars, religious persecution, and enormous social upheaval are some of the extremely unfortunate results.

Some of the religious refugees of these conflicts eventually make their way across the Atlantic to North America. Here, they connect with the Exodus story, claiming this as their new Promised Land and casting themselves as God’s chosen people. In conflicts that arose with Native Americans, other religious factions, or other nations seeking to claim territory, the violent imagery of Revelation guided them to fight with holy righteousness a battle with end-times significance.

Some of these early settlers were Presbyterians, and they eventually got feisty enough to start a revolution. The American Revolution was regarded by the English as a “Presbyterian Rebellion,” and its supporters were often disdained as “those blasted Presbyterians.” Twelve signers of the Declaration of Independence were Presbyterian, including the only clergyman, John Witherspoon.

If you know a bit about Presbyterian polity and a bit about American governance, you’ll find quite a few similarities, not by accident. The same year that the U.S. Constitution was written, Presbyterians adopted our historic principles of church order, which remain in our Book of Order today, and include the following assertions:

- That “God alone is Lord of the conscience, and hath left it free from the doctrines and commandments of men which are in anything contrary to his Word, or beside it, in matters of faith or worship.”

- Therefore we consider the rights of private judgment, in all matters that respect religion, as universal and unalienable: We do not even wish to see any religious constitution aided by the civil power, further than may be necessary for protection and security, and at the same time, be equal and common to all others.

- Ecclesiastical discipline must be purely moral or spiritual in its object, and not attended with any civil effects.

The separation of church and state was enshrined in our Constitution by Presbyterians who also echoed this sentiment in their own ecclesial constitution. They had seen enough violence and bloodshed from the marrying of civil and ecclesial authority, and they did not want it to plague this new nation.

When Paul advocated obedience to civil authority, he was not endowing all governments with divine sanction and power. He was acknowledging that Christians are without a true homeland on this earth, as Hebrews says, “strangers and foreigners on the earth,” desiring “a better country.” And so, while we sojourn here, living as obedient citizens to governments that maintain the common good and restrict evil is faithful living.

What Paul did not say is that we should idolize our nation or its leaders or obey leaders who are evil or unjust or use religion to empower government. He wasn’t advocating for a “Holy Roman Empire,” or for “Christendom,” or for a “Christian Nation.” But this text from Romans has a horrifying history of misuse and abuse. Slaveholders preached this to their slaves. The Nazis preached this to garner support for Hitler. And so, I was shocked and grieved to see this passage being quoted by American Christians in recent years. Strangely, since the 2020 election it seems to have fallen back out of popularity. It would seem that if this passage applies to one American president, it must apply to them all, not just the ones we like.

So it was difficult for me to take up this passage this week and look at it in the context of the relationship between Christianity and American government today. I thought about the civil disobedience of the Suffragettes, the Civil Rights Movement, and the activists for LGBTQ rights, defying the government that oppressed people and restricted their rights. I thought about the resurgence of Christian Nationalism, and how that toxic ideology conflates the authority of God and government, eroding the separation of church and state, and baptizing human causes with divine power. I thought about the most recent statistics on trust in our government, which showed that only two in ten Americans trust the government to do what is right. This number is down a little from last year, but it has been below thirty percent for over a decade.

How can any of us obey a government we don’t trust to do the right thing? How can we faithfully live in a land where we suspect the government does not promote the common good and restrain evil? How can we believe that those authorities have been instituted by God?

First, we need to recognize that, in saying that their authority comes from God, Paul was limiting human authority, not sanctifying it. He did not trust the Roman government that had executed his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, the government that would eventually execute him as well. But he did trust in God and firmly believed in God’s sovereignty over all human institutions and powers. There was comfort for him in knowing that, though Rome might have seemed almighty and the Emperor claimed to be god, the only authority in heaven and on earth is God. Christians running around martyring themselves or killing each other was not going to work out in the long run. So temporary obedience to civil authorities until Christ returned seemed like a much better alternative.

Second, we need to work on trust in this county. We can blame politicians for the erosion of trust and divisiveness we suffer from. But we’re all grown-ups here. If we want politicians we can trust, we can vote for them. If we want to seek peace and unity, we can find ways to do that. Sadly, our City Council this week failed to act on a single recommendation of the Trust Commission they established in response to the Karen Gardner arrest. If we want to rebuild trust in our community, we should all be asking why that happened and what we can do about it.

Finally, the United States is a government designed to be “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” We are those people, and it is our authority that Paul claims is God-given. So the most important thing we can do is ensure that, to whatever degree possible, we are exercising our authority in ways that are faithful to God and loving toward our neighbor. This applies not just to the civil authority we exercise by voting or serving in public office. This applies to the authority we exercise in our workplaces, our families, the boards we serve on, the social circles we influence, even in the church. Instead of figuring out who we should be blaming and bashing, obeying or disobeying, we need to each take a good, hard look at how we’re exercising our own authority in the world.

Throughout history, God’s people have lived within a wide variety of governmental structures – tribal, theocratic, monarchy, imperial, autocratic, democratic. None of these systems have worked out perfectly, and all of them are subject to human frailty and sinfulness. And any of them can be used by God bring about the reign of God on earth. But that is not going to happen by imbuing the government or any of its leaders with divine authority. It will happen through each of us taking responsibility for our own authority, our own participation in systems of government, our own behavior in civil society. When we seek to honor God in those ways, perhaps we will have a government that we can trust and recognize as an agent of God’s authority, God’s love and goodness and grace, in a world that desperately needs such a light on a hill.

To God be all glory forever and ever. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment